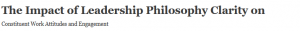

The Impact of Leadership Philosophy Clarity on

Constituent Work Attitudes and Engagement

Te am

Sp irit

C la

rit y

of L

ea d

er sh

ip P

hi lo

so p

hy Low

Constituent Work Attitudes and Engagement

Pr ide

Co mm

itm en

t

Mo tiv

ati on

Ma kin

g a

D iffe

ren ce

Tr us

t

Ma na

ge me

nt

Le

ad er

Eff ec

tiv en

es s

0

5.00 High

4.50 4.00 3.50 3.00 2.50 2.00 1.50 1.00 0.50

the inner confidence necessary to express ideas, chose a direction, make tough decisions, act with determination, and be able to take charge of your life rather than impersonating others.

Let Your Values Guide You

Milton Rokeach, one of the leading scholars in the field of human values, referred to a value as an enduring belief. He noted that values are organized into two sets: means and ends.2 In the context of our work on leadership, we use the term values to refer to here-and-now beliefs about how things should be accomplished—what Milt calls means values. We will use vision in Chapters Four and Five when we refer to the long-term ends values that leaders and constituents aspire to attain. Leadership requires both. When sailing through the tur-

49 C

L A

R IF

Y V

A L

U E

S

bulent seas of change and uncertainty, crew members need a vision of the destination that lies beyond the horizon; they also need to understand the principles by which they must navigate their course. If either of these is absent, the journey is likely to end with the crew lost at sea.

Values influence every aspect of your life: your moral judgments, your responses to others, your commitments to personal and orga- nizational goals. Values set the parameters for the hundreds of deci- sions you make every day, consciously and subconsciously. Options that run counter to your value system are seldom considered or acted on; and if they are, it’s done with a sense of compliance rather than commitment.

Values constitute your personal “bottom line.” They serve as guides to action. They inform the priorities you set and the decisions you make. They tell you when to say yes and when to say no. They also help you explain the choices you make and why you made them. If you believe, for instance, that diversity enriches innovation and service, then you should know what to do if people with differing views keep getting cut off when they offer fresh ideas. If you value collaboration over individualistic achievement, then you’ll know what to do when your best salesperson skips team meetings and refuses to share information with colleagues. If you value indepen- dence and initiative over conformity and obedience, you’ll be more likely to challenge something your manager says if you think it’s wrong.

All of the most critical decisions a leader makes involve values. For example, values determine how much emphasis to place on the immediate interests of the customer or the long-term interests of the company, how to apportion time between family and organizational responsibilities, and what behaviors to reward or discourage. In turn, these decisions have critical organizational impact. Indeed, in these

50 T

H E

L E

A D

E R

S H

IP C

H A

L L

E N

G E turbulent times, having a set of deeply held values allows leaders to

focus and make choices among a plethora of competing beliefs, paradigms, and interests.

Paul di Bari’s operations section within the engineering services group took on the new responsibility for the physical security of the VA Palo Alto Health Care System’s 2.2-million-square-foot facility. Along with the responsibility of hiring a new technician to manage this system, Paul was also taking on a new contractor relationship. Before starting any more projects, Paul called a meeting with the new technician and contractor to figure out the status of the current access system, any open projects, and any projects on the horizon. Paul used this meeting to vocalize his intentions about how the newly developed team would work, his vision moving forward, and his expectations for all parties. His values on project timelines, preparations, submittals, and execution would require more detailed attention than in the past and would also, he hoped, create a new sense of accountability. Paul explained,

If I was going to pay large sums of money for parts and services, then I had expectations for the quality of the deliver- able, which were far higher than the previous regime. These higher standards of quality were necessary to fix the system and to make it operate at a high level. I began to personally inspect the work of the contractor as we completed six open projects. During this time, I was also training our new techni- cian and establishing expectations of project management (for example, statements of work, pricing quotes, communica- tion, workmanship, and the final product) that he would need to carry forth. It was imperative to the long-term success of this program and this new team that I clearly explained what my values were, my project management style and expectations.

51 C

L A

R IF

Y V

A L

U E

S

Paul had to find his voice as a leader by clearly stating his leader- ship principles and the accompanying management goals and objec- tives. At the beginning of the project, Paul met with the contractor and his new technician to communicate these in the context of the security access system. By clearly defining his standards, he was establishing a baseline for future performance and also a measuring block on which to base accountability. “It would have been very easy for me,” Paul said, “to sit back and supervise the program from afar, but in order to earn the trust and respect of both people involved, I had to establish a sense of trust through my work ethic.” Because Paul was clear about his own values, he found it relatively easy to talk about values and subsequently to use them in setting standards and expectations. This tone at the top from Paul provided guidelines for how his constituents would subsequently act and make decisions.

As Paul’s experience illustrates, values are guides. They supply you with a compass by which to navigate the course of your daily life. Clarity of values is essential to knowing which way is north, south, east, and west. The clearer you are about your values, the easier it is for you and for everyone else to stay on the chosen path and commit to it. This kind of guidance is especially needed in dif- ficult and uncertain times. When there are daily challenges that can throw you off course, it’s crucial that you have some signposts that tell you where you are.

Say It in Your Own Words

People can speak the truth only when speaking in their own true voice. The techniques and tools that fill the pages of management and leadership books—including this one—are not substitutes for who and what you are. Once you have the words you want to say,

52 T

H E

L E

A D

E R

S H

IP C

H A

L L

E N

G E you must also give voice to those words. You must be able to express

yourself so that everyone knows that you are the one who’s speaking.

You’ll find a lot of scientific data in this book to support our assertions about each of The Five Practices of Exemplary Leadership. But keep in mind that leadership is also an art. And just as with any other art form, leadership is a means of personal expression. To become a credible leader, you have to learn to express yourself in ways that are uniquely your own. Which is exactly what Andrew Levine did, and in the process helped his colleague Pranav Sharma be able to do the same.

Andrew is a head mentor at the Young Storytellers Foundation (YSF), a nonprofit organization in the United States that provides a creative outlet to fifth-graders whose public schools do not have the budget for creative arts programs. He is passionate about and committed to providing a classroom atmosphere that pushes the imaginations of the kids they mentor, and he cares deeply for all the YSF volunteers. According to one of those volunteers, Pranav Sharma, Andrew’s personal values fit comfortably with the values articulated in YSF’s mission statement. Pranav told us how Andrew influenced him: “He had a unique voice among the mentors. His example led me to exhibit values he shared with the organization. He helped me understand what it meant to the kids to have a unique voice.”

Pranav was paired with a fifth-grader named Rachel, and was tasked to guide her in writing an original story in a ten-page screen- play format, but he was having trouble getting Rachel to focus on her story. Whereas other mentors were making progress on their kids’ stories, Pranav felt that Rachel was not very motivated. The fact that Pranav was absent a couple of times over the eight-week

53 C

L A

R IF

Y V

A L

U E

S

program because of the demands from his workplace didn’t help the situation. Andrew was noticeably frustrated with Pranav and a few other mentors’ seeming lack of interest in the program. He took two steps to remedy the situation. First, he reminded the delinquent mentors why they had joined the program. He talked about why he was loyal to the program. He asked them to leave the program if they were not making YSF a priority, which would be evidenced by future absences. Second, he asked the volunteers to look at the program through the perspective of the fifth-grader. What are the kids looking for from their mentors? He suggested that the volunteers stop wor- rying about whether they were qualified to mentor or whether the kids would like them. All that was required, Andrew explained, was to be present and to talk to them. Pranav got the point.

Andrew was right. He was asking us to affirm our shared values and find our voice. What Andrew was doing was asking us to reexamine the reasons we joined YSF. He wanted us to be vested in YSF’s values, which included words like loyalty, commitment, passion, and patience. He wanted us to build a relationship with the kids by talking to them. The only way to make a unique difference in a kid’s life was to find my own voice. I had to find my voice if I was to make an indelible impression on my mentee.

So Pranav gave it a shot. He reflected on the reasons he had originally wanted to join YSF, which involved giving back creatively to the community. He had wanted to join a nonprofit organization that valued loyalty. He said,

Finding my voice was not easy. I talked without pretense, allowing Rachel to guide the conversation. It was difficult at

54 T

H E

L E

A D

E R

S H

IP C

H A

L L

E N

G E first, but the enthusiasm in Rachel’s eyes encouraged me to

continue to establish my own voice and my own words. The result was a happy child who was proud of her original story. At the end of the program, she gave me a very creative thank-you card highlighting me as the best mentor she had had. I was proud of her.

The lesson here is that Andrew gave Pranav, and all the other mentors, time to discover how their personal values meshed with those of YSF. By telling them his own story of why he was passionate about becoming a mentor at YSF, he helped them find the words to express their own reasons for caring about YSF, its mission, and especially the children. Andrew didn’t tell them what to believe; he told them about his own beliefs and asked them to find in their own values their reasons for being involved with the organization. Through this reflection, they discovered their own voice and found the words necessary to reach kids like Rachel and help them find their way.

Leaders like Andrew and Pranav understand that you cannot lead through someone else’s values or someone else’s words. You cannot lead out of someone else’s experience. You can lead only out of your own. Unless it’s your style and your words, it’s not you—it’s just an act. People don’t follow your position or your technique. They follow you. If you’re not the genuine article, can you really expect others to want to follow? To be a leader, you’ve got to awaken to the fact that you don’t have to copy someone else, you don’t have to read a script written by someone else, and you don’t have to wear someone else’s style. Instead, you are free to choose what you want to express and the way you want to express it. In fact, you have a responsibility to your constituents to express yourself in an authentic manner, in a way they would immediately recognize as yours.

55 C

L A

R IF

Y V

A L

U E

S