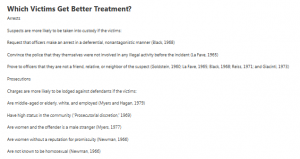

Which Victims Get Better Treatment?

Arrests

Suspects are more likely to be taken into custody if the victims:

Request that officers make an arrest in a deferential, nonantagonistic manner (Black, 1968)

Convince the police that they themselves were not involved in any illegal activity before the incident (La Fave, 1965)

Prove to officers that they are not a friend, relative, or neighbor of the suspect (Goldstein, 1960; La Fave, 1965; Black, 1968; Reiss, 1971; and Giacinti, 1973)

Prosecutions

Charges are more likely to be lodged against defendants if the victims:

Are middle-aged or elderly, white, and employed (Myers and Hagan, 1979)

Have high status in the community (“Prosecutorial discretion,” 1969)

Are women and the offender is a male stranger (Myers, 1977)

Are women without a reputation for promiscuity (Newman, 1966)

Are not known to be homosexual (Newman, 1966)

Are not alcoholics or drug addicts (Williams, 1976)

Have no prior arrest record (Williams, 1976)

Can establish that they weren’t engaged in misconduct themselves at the time of the crime (Miller, 1970; Neubauer, 1974; and Williams, 1976)

Can prove that they didn’t provoke the offender (Newman, 1966; Neubauer, 1974; and Williams, 1976)

And the offender are not both black and are not viewed as conforming to community subcultural norms (Newman, 1966; McIntyre, 1968; Miller, 1970; and Myers and Hagan, 1979)

Convictions

Judges or juries are more likely to find defendants guilty if the victims:

Are employed in a high-status job (Myers, 1977)

Are perceived as being young and helpless (Myers, 1977)

Appear reputable and have no prior arrest record (Kalven and Zeisel, 1966; and Newman, 1966)

Had no prior illegal relationship with the defendant (Newman, 1966)

In no way are thought to have provoked the offender (Wolfgang, 1958; Kalven and Zeisel, 1966; and Newman, 1966)

Are white and the defendants are black (Johnson, 1941; and Allredge, 1942; Garfinkle, 1949; and Bensing and Schroeder, 1960)

And the offender are not both black and are not viewed as acting in conformity to community subcultural norms (Newman, 1966; McIntyre, 1968; Miller, 1970; and Myers and Hagan, 1979)

Punishments

Judges will hand down stiffer sentences to defendants if the victims:

Are employed in a high-status occupation (Myers, 1977; and Farrell and Swigert, 1986)

Did not know the offender (Myers, 1977)

Were injured and didn’t provoke the attack (Dawson, 1969; and Neubauer, 1974)

Are white and the offenders are black (Green, 1964; Southern Regional Council, 1969; Wolfgang and Riedel, 1973; and Paternoster, 1984)

Are females killed by either males or females (Farrell and Swigert, 1986)

V I C T IMS ’ R IG H T S AN D TH E C R IM IN AL JUS T I C E S YS TE M 241

Copyright 2016 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. WCN 02-200-203

overworked and understaffed homicide detectives may carry out only a superficial, routine investiga- tion. For example, the fatal shooting of a street- level prostitute or drug peddler would attract little public notice or official concern and certainly wouldn’t merit the establishment of a task force of detectives to track down the killer who carried out what the police mockingly term a “misdemeanor homicide” (see Simon, 1991; and Maple, 1999).

On the other hand, when a member of the police force is slain, the homicide squad will work day and night to follow up every possible lead in order to catch the killer and reinforce the message that the death of an officer will not go unpunished. To illustrate how law enforcement agencies assign capturing the killer of “one of their own” the high- est priority, consider this comparison: In 1992, police departments across the country solved 65 percent of murders and 91 percent of the killings of fellow officers (FBI, 1993). Similarly, during 1998, 93 percent of line-of-duty officer killings were cleared, compared to 69 percent of civilian murders across the nation (FBI, 1999). And in 2007, right after homicide solution rates sank to an all-time low of 61 percent, 50 out of 51 murders of police officers were cleared by the arrest of a suspect or by exceptional means (the perpetrator was justifiably killed by the dying officer or by other officers, or the assailant afterward committed suicide or died under other circumstances) (FBI, 2008a).

Most of the research cited in Box 7.5 uncover- ing evidence of differential handling was conducted before the victims’ rights movement scored sweep- ing legislative victories. Therefore, victimologists need to carry out a new round of investigations to discover whether the past inequity of differential handling persists to this day, or whether the lofty goals of “equal protection under the law” and “jus- tice for all” are becoming more of a reality in state criminal justice systems across America. As social scientists continue to evaluate the effectiveness of informational and participatory rights that have been granted in recent decades, they are likely to discover evidence of differential access to justice: that certain groups of people are more likely than others to be informed of their rights, to exercise

them, and to use them effectively to influence the decision-making process (see Karmen, 1990).

Even though many legislatures have added vic- tims’ rights amendments to their state constitutions or have passed a victims’ bill of rights, much educa- tional work needs to be done, a study conducted by the National Center for Victims of Crime (NCVC, 1999) concluded. It surveyed victims in two states considered to have strong pro-victim protections and in two states where their rights on paper were limited. Overall, those whose cases were processed by the justice systems of states with strong protection fared better, but even they were not afforded all the opportunities they were supposed to get. In the two states that theoretically guaranteed many rights, more than 60 percent of victims interviewed were not notified when the defendant was released on bail, more than 40 percent were not told the date of the sentencing hearing, and nearly 40 percent were not informed that they were entitled to file an impact statement at the convict’s parole hearing. Of those who found out in time, most (72 percent) attended the sentencing hearing and submitted an impact statement, but relatively few went to bail or parole hearings. Only about 40 percent of the local officials surveyed in the two strong protection states knew about the new laws enumerating victims’ rights (Brienza, 1999; and NCVC, 1999).

Overall, a survey of cases handled by prosecu- tors across the country at the end of the twentieth century failed to find evidence of substantial changes in outcomes resulting from the passage of victims’ rights legislation (Davis et al., 2002).

As a consequence of constraints and obstacles that undermine the effective implementation of victims’ rights, some movement activists remain pessimistic, even cynical about the much-heralded reforms that supposedly grant empowerment. Mere pledges of fair treatment do not go far enough. Being notified about the results of a bail hearing, plea negotiation session, sentencing hearing, or parole board meeting falls far short of actually pur- suing one’s perceived best interests. Attending and speaking out is no guarantee of being taken seri- ously and truly having an impact. Victims still have no constitutional standing, which means that

242 CH APT ER 7

Copyright 2016 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. WCN 02-200-203

they cannot go to civil court and sue for monetary damages if their rights are ignored or violated, and they cannot veto decisions about bail, sentences, and parole that are made in their absence without their knowledge and consent (Gewurz and Mercurio, 1992). Lofty pronouncements that the rights of victims to fair treatment will be carefully respected by officials might prove to be lip service, paper promises, and cosmetic changes without much substance (Gegan and Rodriguez, 1992; and Elias, 1993). However, because recent federal legis- lation grants victims the right to appeal rulings that appear to violate their rights, advocates have con- vinced the Department of Justice to sponsor victim law clinics to work to boost the degree of compli- ance by uninformed criminal justice officials (Schwartz, 2007; and Davis and Mulford, 2008). As of 2011, 12 legal clinics across the country served victims seeking to have their rights respected and enforced in court proceedings (NCVLI, 2011).

What is the ultimate goal of victims’ rights advo- cates? What some seek might be called a system of “parallel justice.” In the aftermath of serious crimes, “justice is served” when offenders are punished and isolated behind bars, and then rehabilitated and even- tually reintegrated into society by reentry programs. But there is no comparable societal response for vic- tims, which would begin with an acknowledgement that what happened to them was wrong, and would culminate with efforts to assist them to rebuild their lives. The guiding principle of parallel justice is that a society has an obligation to its victims too: to help them to heal, regain a sense of security, protect them from further harm, and reintegrate back into the life they were leading before the crime occurred. The public must be mobilized to support a comprehensive approach to making victims whole again that supple- ments the efforts of government agencies with

additional forms of support from private and non- profit groups such as community organizations. Local resources must be marshaled to provide a menu of services that can address both the immediate and the long-term welfare of individuals harmed by interpersonal violence (Herman, 2010).

In order to better provide practical assistance and financial compensation for their losses and expenses, the governmental response should include a nonad- versarial conference in which victims explain what happened to them, the unwanted event’s impact, and what they need to get their lives back on track. The conference should result in an official validation that they have been wronged. Case managers should determine how best to enable them to rebuild their lives with the help of an array of services such as day care, job training, housing, or counseling. Offenders can play a role in constructing a parallel justice system for victims by making restitution and performing community service as part of their own reentry pro- cess (Herman, 2000, 2010; and NCVC, 2008).

One necessary step for an action plan to rebal- ance one-sided criminal justice procedures that exclude victims would be to set up an independent office or commissioner or ombudsperson. This inde- pendent body could monitor actual case outcomes to make sure that individual victims are getting the services and opportunities they are supposed to, according to new laws. It could also identify short- comings in existing procedures that need to be fixed through legislation. Another step forward would entail setting up permanently funded institutes for victims’ rights and services, preferably based at uni- versities that would be centers for research and development. The institutes could assemble data, carry out surveys, and conduct and evaluate social experiments about advocacy and innovative services in order to identify best practices (see Waller, 2011).

SUMMARY

Whether they want to see their attacker punished via incarceration, given effective treatment in some rehabilitation program, or ordered to make restitu- tion, victims might find themselves in conflict

rather than in cooperative relationships with prose- cutors, judges, and corrections officials.

Victims want prosecutors’ offices to provide them with lawyers who will represent their interests

V IC T IMS ’ R IG H T S AN D TH E C R IM IN AL JUS T I C E S YS TE M 243

Copyright 2016 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. WCN 02-200-203

faithfully, but they may be disappointed if the assistant district attorneys assigned to handle their cases don’t take steps to protect them from reprisals, don’t consult with them during plea negotiations, or fail to gain convictions from juries after trials. Victims are not sur- prised if defense attorneys try to wear them down by stalling tactics and try to impeach their testimony by asking hostile questions during cross-examinations at trials. Victims hope that judges will be evenhanded but can become upset if judges set bail low enough for defendants to secure release and then threaten them, and if judges impose sentences that do not reflect the gravity of the offenses that harmed them. Victims

want corrections officials to keep them posted con- cerning the whereabouts of convicts, protect them from reprisals after release, and effectively supervise restitution arrangements that might have been imposed as conditions of probation or parole.

Several decades ago, before the rise of the victims’ movement, insensitive mistreatment by agencies and officials within the criminal justice process was common. Victims from privileged backgrounds clearly were treated much better than others. Researchers need to document whether the system now delivers equal justice for all or if the problem of differential handling persists.